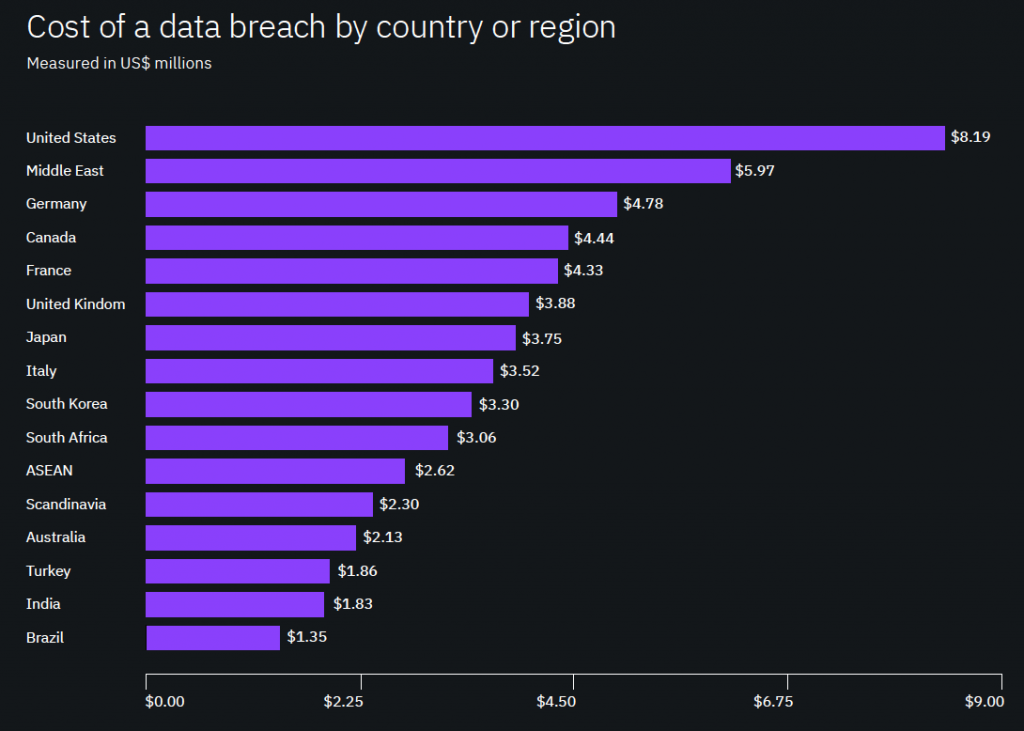

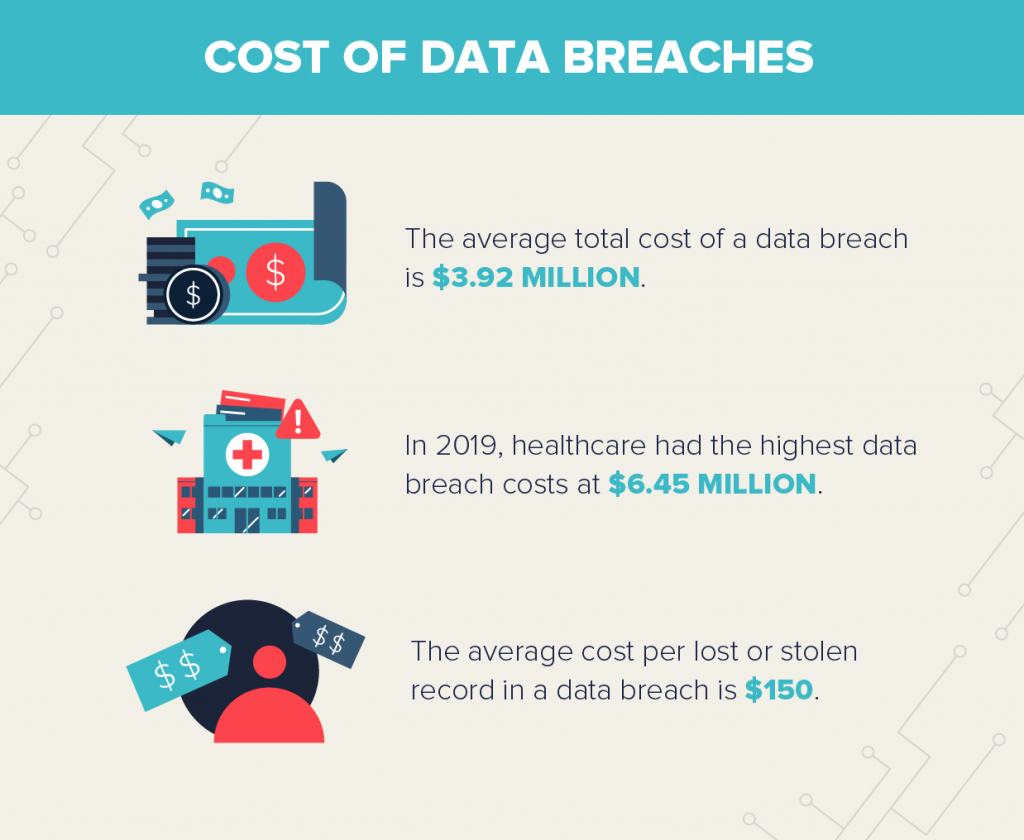

In 2019, the United States held the world record of having the highest average cost per data breach at $8.19 million (IBM Security and Ponemon Institute, 2019), and healthcare data breaches affected 80% more people than just two years prior in 2017. (Statista, 2020). In today’s data-driven environment, it seems not a day goes by without hearing of a data breach or leak. Data privacy in the US is a growing problem caused primarily by the exponential increase of digital data, the trend of moving data storage to the cloud, and lack of a federal data privacy regulation.

Over the past several years, digital data has been increasing at an unprecedented rate. To put it into perspective, in 2019 the overall global population increased at just over 1% to 7.7 billion, while the number of unique mobile phone users increased by 2% to 5.8 billion. In addition, the number of internet users increased 9% to 4.4 billion, which is 57% of the global population. (Hootsuite & We Are Social 2019). As global urbanization continues, the sheer number of people utilizing data in their day-to-day lives will continue to grow. Combining personal use with the fact that nearly all businesses have a website and run their organizations using computers, it becomes clear that the use of data will only continue to increase in the coming years. All of this data, which moves across continents in seconds, needs to be stored and managed somewhere. This exponential increase in the use of digital data has required an equally aggressive increase in data storage capabilities.

Over the past several years, digital data has been increasing at an unprecedented rate. To put it into perspective, in 2019 the overall global population increased at just over 1% to 7.7 billion, while the number of unique mobile phone users increased by 2% to 5.8 billion. In addition, the number of internet users increased 9% to 4.4 billion, which is 57% of the global population. (Hootsuite & We Are Social 2019). As global urbanization continues, the sheer number of people utilizing data in their day-to-day lives will continue to grow. Combining personal use with the fact that nearly all businesses have a website and run their organizations using computers, it becomes clear that the use of data will only continue to increase in the coming years. All of this data, which moves across continents in seconds, needs to be stored and managed somewhere. This exponential increase in the use of digital data has required an equally aggressive increase in data storage capabilities.

As digital data increases, so does the trend of moving data storage to the cloud. Often misunderstood, the cloud is not some mystical Cumulus floating in the sky with ones and zeros suspended in it. Rather, the cloud is nothing more than large data centers that house racks and racks of servers and drives that run 24/7. These constantly moving parts create an immense amount of heat, so data centers utilize massive cooling mechanisms to keep temperature down. Understandably, data centers therefore use an excessive amount of energy, making operation fairly expensive. While larger businesses previously owned their own data centers or used in-house data storage, there has been a rapid shift to cloud service providers over the past five years. From 2017 to 2019, the number of cloud service data centers rose from 7,500 to 9,100, with 2020 expecting to see that number top 10,000. On the flip side, there were 35,900 data centers owned by non-technology firms in 2018, and that number is expected to significantly decline to 28,500 by the end of 2020. In fact, it is expected that the number of large companies in North America shifting away from using their own data centers to cloud service providers will increase from 10% in 2017 to 80% by 2022. (Loten, A. 2019). The move to cloud service providers is further evidenced by the increasing number of mergers and acquisitions in the cloud service sector. But how does this affect data privacy? It puts the onus of maintaining data privacy into the hands of technology giants rather than individual organizations who know that a breach could literally destroy their businesses. As data increases exponentially and its storage shifts inexorably to the cloud, concerns over data security and privacy escalate in parallel, leading to much-needed data privacy legislation.

As digital data increases, so does the trend of moving data storage to the cloud. Often misunderstood, the cloud is not some mystical Cumulus floating in the sky with ones and zeros suspended in it. Rather, the cloud is nothing more than large data centers that house racks and racks of servers and drives that run 24/7. These constantly moving parts create an immense amount of heat, so data centers utilize massive cooling mechanisms to keep temperature down. Understandably, data centers therefore use an excessive amount of energy, making operation fairly expensive. While larger businesses previously owned their own data centers or used in-house data storage, there has been a rapid shift to cloud service providers over the past five years. From 2017 to 2019, the number of cloud service data centers rose from 7,500 to 9,100, with 2020 expecting to see that number top 10,000. On the flip side, there were 35,900 data centers owned by non-technology firms in 2018, and that number is expected to significantly decline to 28,500 by the end of 2020. In fact, it is expected that the number of large companies in North America shifting away from using their own data centers to cloud service providers will increase from 10% in 2017 to 80% by 2022. (Loten, A. 2019). The move to cloud service providers is further evidenced by the increasing number of mergers and acquisitions in the cloud service sector. But how does this affect data privacy? It puts the onus of maintaining data privacy into the hands of technology giants rather than individual organizations who know that a breach could literally destroy their businesses. As data increases exponentially and its storage shifts inexorably to the cloud, concerns over data security and privacy escalate in parallel, leading to much-needed data privacy legislation.

In 2018, the European Union (EU) implemented the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in an effort to protect the privacy of European consumers. And while Canada had implemented the similar Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) in 2000, GDPR proved to be far more aggressive legislation both in terms of reach and monetary penalty. GDPR requires that all organizations that do business with EU citizens adhere to the legislation, meaning that global organizations such as Apple, Facebook, and Google, as well as smaller US companies that sell to Europeans, are required to follow GDPR. Since its inception in May of 2018, GDPR has leveraged hundreds of millions of Euros in fines and is only getting more aggressive with enforcement; however, GDPR only affects organizations that have dealings with EU citizens. Conversely, the United States has fallen behind in data privacy legislation, leaving the onus of maintaining data privacy to individual states. As of February 2020, only California, Nevada, and Maine have implemented data privacy legislation, with only the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) requiring deletion of personal data if requested, similar to GDPR. (Noordyke, M. 2020). Considering that well over half of all global data breaches occur in the United States and, as previously discussed, those breaches are increasing due to the exponential increase in global data, the lack of a federal data privacy law is concerning. Unlike their European counterparts, Americans are largely left to their own devices when it comes to data privacy and have little recourse when a breach occurs. In fact, one of the largest breaches of 2012 occurred with major online retailer Zappos, affecting 24 million customers. In 2019, the agreed upon settlement to a class action lawsuit provided reparation to the affected individuals in the form of a 10% Zappos discount code that was only good through 31 December 2019. Needless to say, a 10% discount code (which actually helps Zappos rather than punishes them) in exchange for breached personal data hardly seems equitable. (Doe, D. 2019). Until the United States takes federal data privacy as seriously as their European and Canadian counterparts, the privacy and security of American citizens will continue to erode.

In 2018, the European Union (EU) implemented the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in an effort to protect the privacy of European consumers. And while Canada had implemented the similar Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) in 2000, GDPR proved to be far more aggressive legislation both in terms of reach and monetary penalty. GDPR requires that all organizations that do business with EU citizens adhere to the legislation, meaning that global organizations such as Apple, Facebook, and Google, as well as smaller US companies that sell to Europeans, are required to follow GDPR. Since its inception in May of 2018, GDPR has leveraged hundreds of millions of Euros in fines and is only getting more aggressive with enforcement; however, GDPR only affects organizations that have dealings with EU citizens. Conversely, the United States has fallen behind in data privacy legislation, leaving the onus of maintaining data privacy to individual states. As of February 2020, only California, Nevada, and Maine have implemented data privacy legislation, with only the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) requiring deletion of personal data if requested, similar to GDPR. (Noordyke, M. 2020). Considering that well over half of all global data breaches occur in the United States and, as previously discussed, those breaches are increasing due to the exponential increase in global data, the lack of a federal data privacy law is concerning. Unlike their European counterparts, Americans are largely left to their own devices when it comes to data privacy and have little recourse when a breach occurs. In fact, one of the largest breaches of 2012 occurred with major online retailer Zappos, affecting 24 million customers. In 2019, the agreed upon settlement to a class action lawsuit provided reparation to the affected individuals in the form of a 10% Zappos discount code that was only good through 31 December 2019. Needless to say, a 10% discount code (which actually helps Zappos rather than punishes them) in exchange for breached personal data hardly seems equitable. (Doe, D. 2019). Until the United States takes federal data privacy as seriously as their European and Canadian counterparts, the privacy and security of American citizens will continue to erode.

Data privacy and security is a serious and growing global issue, even more so in the United States where the bulk of data breaches occur. As more and more people embrace technology, the need for data storage increases, increasing the need for larger and faster data centers. Additionally, the dramatic shift from on-premise to cloud storage only exacerbates the problem of data privacy by relying on technology giants to protect organizations’ consumer data. Breaches will only escalate in line with our digital footprint, of that there is no question. Without a federal data privacy law, the privacy of American citizens’ data will continue to be at serious risk. And 10% off a pair of shoes simply isn’t the answer.

Heidi White is Director of Marketing at SEM and is a self-proclaimed data security fanatic. Contact Heidi at h.white@semshred.com.

References

IBM Security and Ponemon Institute (2019). Cost of a Data Breach Report. Retrieved from https://www.ibm.com/security/data-breach

Statista (2020). Number of U.S. residents affected by health data breaches from 2014 to 2019. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/798564/number-of-us-residents-affected-by-data-breaches/

Hootsuite & We Are Social (2019), Digital 2019 Global Digital Overview. Retrieved from https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2019-global-digital-overview

Loten, A. (2019, August 19). Data-Center Market Is Booming Amid Shift to Cloud. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/data-center-market-is-booming-amid-shift-to-cloud-11566252481

Noordyke, M. (2020). US State Comprehensive Privacy Law Comparison. Retrieved from https://iapp.org/resources/article/state-comparison-table/

Doe, D. (2019, October 18). Zappos data breach settlement: users get 10% store discount, lawyers get $1.6m. Retrieved from https://www.databreaches.net/zappos-data-breach-settlement-users-get-10-store-discount-lawyers-get-1-6m/